Dear Readers,

The Covid 19 Pandemic provided us with much time to reflect upon our lives, and even our chosen professions. I always assumed that our profession has evolved over the decades to “state of the art” teaching and instruction, grounded in sound reasoning and research. Yet, veteran teachers continue to talk about a “pendulum” that swings back and forth between direct instruction and more progressive methods.

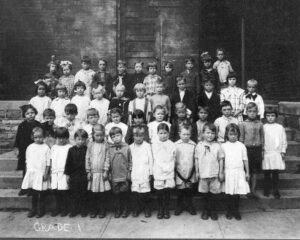

So, I decided to do some research, and even include some family archival records to determine how we have changed over the past 100 years. The result is a piece I’ve entitled: “Then and Now: How Different is Reading and Writing Instruction Today? I hope you enjoy it!

Then and Now: How Different is Reading and Writing Instruction Today?

(Willard School, Perry, Iowa, 1914. John M. Robertson, my father, is fifth from the left in the top row.)

Introduction

Historical narratives allow us to appreciate the rich legacy of our profession, and to imagine possibilities for teaching in the 21st century. In this piece, I focus upon the preparation and supervision of teachers, and the instructional materials for teaching reading and writing in the 1920s. Family photos, primary source documents, archival photographs, and Ancestry records were part of the inspiration for this piece. Vintage textbooks helped to frame an analysis of differentiated language arts instruction one hundred years ago. Issues of constancy, change, and teacher resiliency are examined, with implications for contemporary teaching and learning.

The 1920s

The 1920s was a time of optimism and progressive thinking in education. However, it was also a time when Americans strove to reclaim a sense of normalcy in their lives. The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, which lasted until December of 1920, claimed approximately 650,000 lives in the United States. Urban and rural families lost parents, children, friends, and relatives. Emotions were raw, and further compounded by World War I fatigue. Consequently, issues related to home and family took precedence in most people’s thinking.

Waves of newly arrived immigrants made people anxious about their own job security. In general, the populace was totally unprepared for the stock market crash of 1929, and the “Decade of Depression” that would follow. The 1920s was literally the calm before that economic storm.

My Father’s Story

My father, John M. Robertson, grew up in the mid-western town of Perry, Iowa. 1920 census records report that nearly all residents spoke, read, and wrote in English. Everyone on the census claim the United States as their country of birth. Many “heads of the household” were listed as farmers, but others are recorded as linemen, brakemen, engineers, conductors, or laborers for the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railroad. My grandfather, Charles, was a lineman/maintainer.

In 1920, my father would have been ten-years-old. He would have known all about trains, riverboats, and the “Wild West.” He could have told you how to set up a camp site, that the Mississippi river ran all the way from Perry to New Orleans, how to swim against a river’s current, and even how to “break a bronco.” He would have been familiar with the Jesse James and James Younger gangs, as his grandmother lived in the vicinity of the gangs’ first, successful train robbery. His report cards show he was an average to above average student. Of particular note is that fact that only 78% of children between the age of five and seventeen were enrolled in school at this time. Many students left school after eighth grade to help support their families, as Child-Labor Laws were not enacted until 1938.

There were no integrated schools in the 1920s, and schools were classified as either “white” or “colored.” Moreover, only Black teachers were permitted to teach in the “colored” schools. Over this decade, an 5000 additional schools would be built for Black children in the South.

Teaching Philosophies of the 1920s

The progressive movement, spearheaded by John Dewey (1916), paved the way for experiential and individualistic approaches to the teaching of readers and writers in the 1920s. Dewey highlighted the role of the learner in the process, and further acknowledged that students learn differently. Thus, he proposed they be taught with materials suitable for their strengths and needs. As a result, educators began to reconsider the value of basic reading and writing instruction to individualize instruction and create future productive citizens. Educators began to re-conceptualize teacher preparation, instructional materials, and the modernization of their classrooms. In doing so, they strove to apply a vast body of educational research to classroom practice. The major research topics of this time were: reading interests; reading disability; and readiness for beginning reading (Banton Smith, 1985, p. 256).

The gradual transition in thinking is evident in educational textbooks from the 1920s through 1930s, which were a mix of traditional and progressive ideas about teaching children to read and write. In the literature between 1918 to 1924 two topics were frequently discussed. They were: the preparation and supervision of teachers; and remedial reading (Banton-Smith, 1965, p. 195).

Preparation and Supervision of Teachers

Teacher Manuals

Teacher manuals or professional books of this decade, started to have more form and substance. Paper covered pamphlets and teacher editions were replaced with cloth bound books differentiated for each grade level. Essential elements of these manuals included scientific investigation and learning theories; reading objectives; pre primer methods; procedure by lessons or stages of development; word recognition and phonetics; tests; individual needs; and remedial work. Instructions were less dogmatic in these manuals, and teachers had flexibility in planning instruction and integrating enrichment activities. The first-grade grade teacher manual contained instructions for the primer and first reader. Instructions for second and third graders were combined in a single book, as were those for fourth, fifth, and sixth graders (Banton-Smith, 1965, p. 208).

Student Basal Readers

According to Banton-Smith (1965), “supplemental books never before had been so abundant, so beautiful, or so varied in content” (p. 209). The pre-primer was an innovation of this time period, and considered a foundational preparation for the series of readers that would follow in the subsequent grades. The authors took into account the limited word recognition of young children who were just learning to read, therefore, there were fewer words in each sentence. Pre-primer and primary texts were highly repetitive to promote word recognition. Standard word lists were the basis for the selection of vocabulary for each story (p. 217).

Reading Instruction

Methods for teaching beginning reading were varied, and included: reading stories composed by the children; reading and carrying out direction sentences; dramatizing stories; learning and reading rhymes, and reading from prepared charts containing the primer vocabulary (Smith, 1965, p. 232). Sets of small books (pre-primer to grade six), included realistic narratives, old tales, modern fanciful tales, informational selections, poetry, fables, and silent reading exercises. As an example, first graders read texts such as The Just So Stories, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, and Alice in Wonderland. There were also workbooks for “silent reading and directed study” seat work (Wheat, 1923, p. 223).

A major shift in pedagogical thinking was a move away from expressive oral reading to silent reading for “thought-getting.” In The Teaching of Reading (1923), Wheat describes the various phases of reading instruction, with an emphasis upon silent reading for idea generation. Reading for meaning was the prevalent ideology of the 20s, and phonics was characterized as an instructional strategy of “no value” (Banton- Smith, 1965, p. 233).

Yet, a review of the scope and sequence of teacher manuals reveals that fluency, letter, and word identification activities were still integrated. In general, however, phonics was taught more moderately, and subordinated to other “general reading skills” (p. 235). These skills were: comprehension, retention, interpretation and appreciation, organization, and research. In addition, “specialized skills” were developed that included: understanding the meaning and use of technical vocabulary; reading word problems; and knowing how to record and report observations and experiments (p. 237).

Writing Instruction

It is apparent from archival records that writing instruction was traditional, with a continued emphasis upon composition, grammar, spelling, and penmanship (Wheat, 1923, p. 166). The Palmer Method was the most popular approach for teaching cursive writing. Children learned to print before learning cursive writing, and the latter was usually taught in a separate class. However, the use of students’ own dictated stories based upon their personal experiences was an innovative approach to reading/writing instruction introduced in the 1920s. It would later be known as the “language-experience” approach.

Remedial Reading

The Characterization of “Backward Pupils”

The shift in the concept of individualized instruction, generated by progressives, though ostensibly noble, resulted in the division of students within classes. Individualization, combined with the increased advocacy for mental intelligence tests with Binet equivalents in public schools, led to the specific categorization of students. Students were generally grouped as “poor, average, and superior” (Wheat, 1923, p. 243) in ability. Dewey asserted that grouping based upon test scores was a threat to democracy

Wheat (1923) proposes “special help for backward pupils” or those with “degrees of backwardness.” He characterizes one second grader as “backward” because of his “lack of familiarity with printed words and an utter lack of phonetic power.” Similarly, the degree of a fourth grader’s backwardness was related to the number of repetitions he makes while reading out loud. He writes, “Getting no meaning from the sentence as he phrased it, he repeated in an attempt to get something from the sentence by the second reading (p. 315).”

Word study for recognition, pronunciation, and comprehension of difficult words was the recommended intervention for students with “various kinds of backwardness.” Remedial work included “eye training and focus,” including “flash cards” and “flashing phrases,” “lessons in focus and accuracy,” reading “perfectly” until no errors are made; “breathing exercises,” since “practice in breath control is related to the problem of meaning and interpretation;” and “articulation exercises for “mumblers” or those with other bad speech habits” (Wheat, p. 316). In the early 1920s terms such as “handicapped foreign” enter the discourse. Immigrant children were also characterized as “backward” because of their “meager vocabularies.”

Concluding Thoughts About the 1920s

Teachers in the 1920s did their best with what they had, and enriched language arts instruction through multiple approaches and varied materials. It should be noted that they were given professional leeway to make these decisions. Concurrently, the field of special education was emerging in response to calls for the differentiation of instruction for diverse populations of students. Teachers began to consider new child descriptors, such as “backward” and “word blind,” (the first descriptor for dyslexia) and what it meant for the students in the classrooms.

In addition, these resilient teachers applied “modern classroom” research about silent reading for literacy instruction. Simultaneously, integrating traditional phonics approaches and word study when they felt they were necessary. Not much was known about second language acquisition in the 1920s. There were few research studies about the teaching of “handicapped foreign” students. The selection of the term “handicapped,” demonstrates a deficit perspective about immigrant children. I tend to believe that if the classroom teacher was a child of immigrants herself, this classification would have been abhorrent. Considering the number of students in teachers’ classes, it is incredible that they were able to nurture the literacy development of the readers and writers in their charge at all.

Not every student continued their education after eighth grade or high school, choosing to pursue apprenticeship pathways in varied fields. Social, economic, and political factors played a significant role in their decisions. However, students from the 1920s, would come to be described as “the greatest generation.” The influence of their teachers can never be underestimated.

Teaching Today

A vast and expanding number of landmark studies have greatly influenced language arts instruction since the 1920s. Echoes of Dewey’s sentiments reverberate in today’s calls for student discovery, self-directed learning, and personalized approaches that address the whole child. Personalized learning in the 21st century has become highly computerized, and the teacher’s role is changing. Chalk boards, overhead projectors, TV carts, and cursive writing worksheets have been discarded and replaced with instructional technology, such as Smart Boards, iPads, and eResources.

Preparation and Supervision of 21st Century Teachers

Teacher preparation and supervision continues to receive scrutiny at the state and national level. There is an increased focus upon “evidence-based” teacher educator programs. The Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP), determines if teachers are “classroom ready” to meet the instructional needs of diverse student populations. Issues related to equity, justice, educational technology, and culturally responsive teaching are scrutinized in their accreditation reviews. These concepts are congruent with contemporary research in the field of literacy studies.

Today’s teachers are knowledgeable about content and pedagogy. The ways they organize their classrooms display their beliefs about the role of conversation and collaboration in student learning. They have adopted a process approach to the teaching of reading and writing that involves teacher modeling, mentor texts, and student’s active involvement in lessons. As in the 1920s, more traditional approaches sometimes supplement instruction. Teachers remain resilient and creative in the ways they implement “evidenced based” and strategies instruction in their own literacy classes, and the ways in which they use standardized materials to promote learning for their students.

Teacher Manuals and Student Readers

Teachers from the 1920s might recognize the formatting, scope and sequence of today’s standardized literacy programs. These mass-produced teacher manuals are pleasingly designed and integrate the latest “evidence” to support instructional approaches. Educators from one hundred years ago would marvel at the comprehensive resources that integrate technology with literacy instruction. The digital learning curve would be steep for them, but the teaching approaches would seem familiar.

Twenty-first century readers are appealing in appearance and abundant in supplementary materials. I’m not sure if teachers from the 1920s would think these readers are of quality, as they focused upon the classics. After reviewing them, however, they could easily perceive how the readers increase in complexity for each grade level. The practice of leveling books for guided reading would be a new concept for them. Today’s teachers understand the progression and characteristics of each text level, and use them appropriately to promote students’ reading competencies. Contemporary classroom libraries provide students with access to all levels of books throughout the school day.

In many urban and suburban school districts, computerized literacy programs (Raz Kids, Reading A-Z, Epic, or MyOn), have been adopted. These digital reading programs permit teachers to assign the same passage, but at varied levels of difficulty, to their guided reading groups. It should be noted that the depth, breadth, and quality of the writing at the lower levels passages is significantly inferior, which makes comprehension more difficult. Meager texts do not allow students to use multiple strategies to understand what they are read.

Reading Instruction

Read alouds are still popular with teachers as an instructional strategy, as they promote student engagement, interest, and model fluent reading. However, these shared readings now focus upon critical comprehension skills through open-ended student discussions. Students are encouraged to share what they notice or wonder about a text, and to make connections to their own lives. These classroom conversations create a necessary space for students to express their thinking and questions about literature, and give teachers the opportunity to “unpack” the layers of meaning students might not notice (2019). Through think alouds, teachers model the multiple strategies proficient readers utilize, and ways to pay attention to an author’s cues, These cues assist them summarize and determine a story’s theme. Teachers utilize a the “gradual release of responsibility” (2009) model of instruction to support apprentice literacy learners.

Comprehension instruction has evolved. Independent reading is now considered a meaning making process, in which the reader is actively involved in using graphophonic cues, predicting, inferring, connecting, summarizing, visualizing, self-monitoring, and questioning the text for understanding. Each reader “transacts” (Rosenblatt, 1978), or responds to a text in unique ways. Student schema is as individual as a thumbprint.

The cognitive nature of the reading process is affirmed when tracking students’ miscues, or unexpected responses to a text, when reading aloud. Students invariably substitute a noun for a noun, a verb for a verb, and an adjective for an adjective when they miscue. Readers do not utter random responses, rather, they reread for confirmation, and self-correct miscues that don’t make sense (Goodman, 1996). Therefore, the “backward readers” of the 1920s would not be characterized as such today.

Writing Instruction

Much of today’s writing instruction is geared to the genre that students will face on state standardized texts, so they are taught to write opinion or argument pieces that cite evidence from textual sources. Teachers from one-hundred years ago would be surprised to see the role that standardized tests have played in classroom instruction, as assessments were just being introduced in their schools.

To teachers’ credit and resilience, they have also integrated a process or descriptive approach to teaching writers, and integrated personal narratives to provide students with a writing voice. In similar fashion, students are encouraged to learn the “habits and processes” of a writer, how to analyze an author’s craft, or descriptive language and structural formats. Teachers use think alouds with mentor texts, to model and highlight an author’s techniques, and to co-write with their students. This is reminiscent of the “dictated stories” of the 1920s.

Reading Intervention

The Characterization of “Struggling Readers”

Labels for students have not gone away. Instead, they have changed from “backward” to “struggling” or “at risk.”. Despite the fact that we know so much more about the ways the brain processes information, the nature of the reading and writing processes, and the social and emotional factors that impact upon achievement, the onus for failure continues to be placed upon the student who is performing below grade level expectations. Educators need to examine the types of texts students are asked to read, the literacy tasks they are required to complete, and the presence or absence of teachers’ motivational mindsets when assessing and evaluating student achievement and progress.

English Language Learners (ELLs), English as a New Language (ENL) Learners, Bilingual and Multilingual Learners

Similar deficit perspectives about the limited vocabulary of bilingual, multilingual, and English Language Learners, and its correlation to reading and writing struggles are present in today’s research. Over emphasis upon assessment through standardized tests, rather than classroom teachers’ assessments, have exacerbated the situation. Consequently, ELL, ENL, Bilingual or multilingual students are often referred to special education. A teacher shared her frustrations with me, and the fact that her district has been “red-flagged” for this placement practice. We are still striving to develop culturally and linguistically appropriate strategy instruction in reading and writing for children whose first language is not English (Hoover, J.; et al., 2019). Additional historical overviews might focus upon special education “red flags,” and the populations of students who have been traditionally misplaced and disadvantaged through this classification system..

When the Unexpected Happens

The most striking similarity between the 20s and now, is the devastating impact of a pandemic upon families,’ students,’ and teachers’ lives. Life could not continue “as usual.” During the Spanish Flu quarantine schools were briefly closed, and teachers sent home work packets to families. Twentieth-century educators attempted to continue instruction and provide reinforcement activities electronically. However, just as the people living in 1920 were totally unprepared for the Great Depression, teachers and administrators were totally untrained for virtual learning. From March to June of 2020, students joined their classmates and teachers through Google, ZOOM, app-based learning, and other learning platforms. This historic closing of schools, affected 50.8 million public school students. Teachers simultaneously designed digital units of study, while learning how to manipulate the “bells and whistles” of virtual platforms. They were often asked to use multiple platforms, as school systems realized some were better than others.

Children without access to Wi Fi or a computer were shortchanged in this process. Districts reported a lack of Chrome books or iPads for all. Students who were fortunate enough to get a device, might have had to share it with four other siblings. Children who were transitory residents in a school district, or living in shelters had no chance. One teacher shared her concerns that some of the children had just “disappeared,” and could not be contacted by phone or email.

Teaching has always been a vocation, and teachers have always been resilient. We are compassionate and knowledgeable. We understand the importance of creating safe and supportive learning environments for our students. We do what needs to be done, with minimal resources. So much of a teacher’s salary is directed towards purchases for the classroom.

In the summer of 2020, I spoke with an educator who was asked to begin a summer program aimed at helping her special education students “catch up.” She stated, “Their desks will be six feet apart, and they asked me to wear a mask. The students don’t have to wear them, just me! I want to wear a transparent face shield so the kids can see my mouth when I talk. The other masks will frighten them.” We talked for quite a while and agreed that is the most sensible option. Her students, like all students, need that personal connection/relationship with the teacher. So, teachers will make it happen like we’ve always done!

Bibliography

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: Free.

Rosenblatt, L.M. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press.

Smith, N. B. (1965). American reading instruction. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Wheat H. G. (1923) The teaching of reading: A textbook of principles and methods. New York: Ginn and Company.

The Coronavirus Spring: The Historic Closing of U.S. Schools (2020). Retrieved from